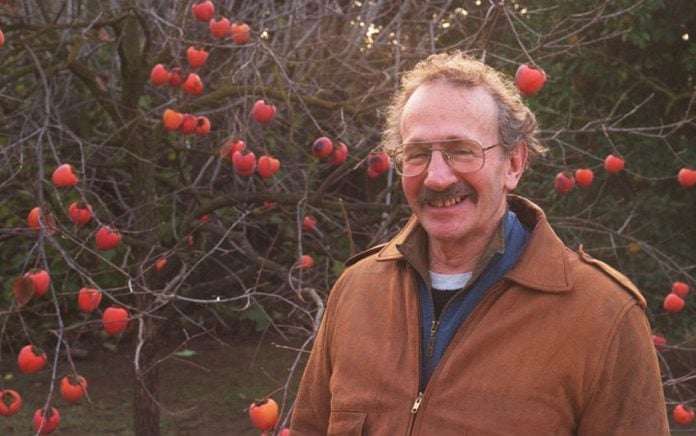

Philip Levine (1928-2015) fue un profesor y poeta norteamericano de ascendencia judía nacido en Detroit. Estudió en la Universidad Estatal de Wayne y posteriormente dictó clases durante más de treinta años en la Universidad Estatal de California. Su poesía retrata la clase obrera americana de mediados del siglo XX con un lenguaje coloquial y preciso que oscila entre la representación de la realidad inmediata y la íntima. Entre sus principales libros publicados se encuentran What work is, ganador del National Book Award en 1991, considerado por la crítica uno de los libros de poesía más importantes de nuestro tiempo; The simple truth (1994), merecedor del Premio Pulitzer de Poesía en 1995. Otros de sus títulos son Stranger to nothing: Selected poems (2006) y The last shift (2016), publicado póstumamente. Fue elegido Poeta Laureado de los Estados Unidos en el año 2011. Murió a la edad de 87 años.

Soñando en sueco

La nieve cae sobre los altos y pálidos juncos

cerca de la costa, y aunque en algunos sitios

el cielo es pesado y oscuro, un claro sol

se asoma lanzando su luz amarilla

sobre la superficie de las olas que llegan.

Alguien ha dejado una bicicleta apoyada

contra el tronco de un arbusto y se adentra

en el bosque. Las huellas de un hombre

desaparecen entre los densos pinos y robles,

un hombre lento, de pies grandes, arrastra

su pie derecho en ángulo extraño

mientras marcha a la única cabaña blanca

que envía su columna de humo al cielo.

Debe ser el cartero. Una bolsa de lona,

medio cerrada, se levanta derecha en una caja de madera

sobre la rueda delantera. Los dispersos

cristales de nieve se filtran uno a uno

empañando la dirección de una sola carta,

aquella que escribí en California y envié

a pesar de saber que no llegaría a tiempo.

¿Qué tiene que ver con nosotros esta orilla

cercana a Malmö, y la blanca cabaña

sellada contra el viento, y la nieve

cayendo todo el día sin propósito

o necesidad? Ahí está nuestro saco de lona de respuestas,

si sólo pudiéramos conectar las cartas entre nosotros.

La simple verdad

Compré un dólar y medio de pequeñas patatas rojas

Las llevé a casa, las herví en sus cazuelas

Y las comí en el almuerzo con un poco de sal y mantequilla.

Luego caminé por los áridos campos

al borde del pueblo. A mediados de junio

la luz se agarraba de los oscuros surcos a mis pies,

y en la montaña de robles escuché las aves

reunirse para la noche, los arrendajos y sinsontes

graznaban de aquí para allá, los pinzones aún se precipitaban

a la luz polvorienta. La mujer que me vendió

las patatas era de Polonia; ajena a mi infancia,

vestida con abrigo de lentejuelas y gafas

que alcanzaban la perfección de todas sus frutas y vegetales

situados al borde de la calle, me incitaba a probar

el más crudo, pálido y dulce maíz, traído,

juró, de New Jersey. “Come, come”, dijo ella,

“Aunque no lo hagas diré que lo hiciste”.

Algunas cosas

las sabes toda tu vida. Son tan simples y verdaderas

que deben ser dichas sin elegancia, metro o rima,

deben colocarse sobre la mesa al lado del salero,

del vaso de agua, de la ausencia de luz aglutinándose

en la sombra de los marcos, deben estar

vacías y desnudas, deben valerse por sí solas.

Mi amigo Henri y yo llegamos a esto juntos en 1965

antes que me alejara, antes que él empezara a matarse,

y ambos a traicionar nuestro amor. ¿Puedes saborear

lo que digo? Son cebollas o patatas, una simple

pizca de sal, el exceso de mantequilla derritiéndose

es innegable, se queda detrás de la garganta como una verdad

que nunca se dice porque el momento siempre es inadecuado,

se queda ahí por el resto de nuestras vidas, impronunciable,

hecha de esa suciedad que llamamos tierra, del metal que llamamos sal,

en una forma para la que no tenemos palabras, y así vivimos.

La voz de mi hermana

Medio dormido en mi silla, escucho

una voz temblar en la ventana,

el mismo llanto de miedo que sentí

por vez primera junto al Guadalquivir

cuando me despertó el viento y la lluvia,

cuando llamé a alguien ausente,

y escuché la respuesta. Eso fue en España,

veintiséis años atrás. Su voz,

la de mi hermana, viene de nuevo

a preguntar cómo seguimos sin ella.

Esa noche junto al gran río

me vestí en la oscuridad, solo

dejé a mi familia y caminé congelado hasta

la llegada del atardecer, al borde oriental

de las montañas. No encontré respuesta

o aprendí a no preguntar, porque

el viento responde si uno espera

lo suficiente. Gira en una dirección,

luego en otra, los árboles se tuercen,

se levantan, la vasta hierba se ondula y reverencia,

todas las voces que has escuchado

las escuchas otra vez hasta saber

que nada has escuchado. Así espero,

inmóvil, y mientras se calma el viento

crece silenciosa mi pequeña, perdida

hermana, tímida como en vida.

Recuerdo haber regresado esa noche

en Sevilla, pasados los rieles,

tratando de aferrarme a cada palabra

pronunciada por ella, aunque se escaparan

de mis labios sus palabras. Las máquinas

humearon en el frío. El centinela

de gorra marrón se sacudió

para despertar, y sin fuego,

llanto humano o canto de ave,

el día se quebró sobre todas las cosas.

No pidas nada

En lugar de recorrer solo la noche

saliendo de la ciudad hacia los campos

dormido bajo un cielo oscurecido;

el polvo que levantan tus pasos

se transforma en una dorada lluvia

que cae sobre la tierra como

el regalo de un dios desconocido.

Los sicomoros en la orilla del cauce,

los pocos álamos del valle,

contienen su aliento mientras cruzas el

puente de madera que no te lleva

a ningún lugar en el que hayas estado, pues

este paseo se repite una o más veces al día.

Es por eso que ves en la distancia

más allá de la primera cumbre de colinas bajas

donde nada crece, hombres y mujeres

a horcajadas en mulas, en caballos, algunos

a pie, toda la familia perdida que

nunca rezaste para ver, reza por verte,

salmodiando y cantando para atraer

la luna al último rayo de sol.

Detrás de ti las ventanas del pueblo

parpadean, las casas se cierran;

hacia adelante las voces se disipan como

música en agua profunda y desaparecen;

incluso los veloces, inquietos pinzones se han

convertido en humo, y el único camino blanqueado

en luz de luna conduce a cualquier lugar.

Polvo y memoria

Un hombre pequeño sin afeitar, tal vez en

sus cincuenta, con una gorra arrastrada a un lado

para ocultar sus rasgos. Inclinó su cabeza

hacia el suelo, gimió, se levantó para dejarla caer

en abandono, y arrojó su cuerpo hacia

adelante otra vez. ¿Un suplicante

de rodillas ante qué? ¿Ante el abuso

de la tierra y el mar? ¿Ante el poder del dolor?

¿Ante el rostro de una diosa pintado en la proa

del barco de pesca en cuya sombra se escondió?

Cuando la gorra cayó reconocí un hombre

con el que me cruzaba volviendo a casa cada noche,

un vecino cercano con el que nunca he hablado

ni hablaré. Después del anochecer no me volví

para mirar y encontrarlo ausente o para escuchar

el mar, sin luna, en una palabra

sin consonantes, repetida invisiblemente

dentro de mi cabeza.

¿De qué se trata esto?

Dondequiera que estés ahora hay tierra

en algún lugar debajo de ti esperando tomar

lo poco que dejes. Esta mañana me levanté

antes del amanecer, vestido en el frío, lavé

mi cara, pasé un peine por mi pelo

y sentí mi cráneo debajo, implacable,

pronto el hogar de nada. El viento

que arremolinó la arena ese día años atrás

tuvo un nombre que sobrevivirá al mío

por mil años, aunque hecho de aire,

que es en lo que me convertiré, con suerte,

dice en voz baja a tu oído,

“soy polvo y memoria, tus dos vecinos

en esta estrella fría.” Ese viento, el Levante,

aullará por las cuencas de mi cráneo

para hacer una música peculiar. Cuando la escuches,

recuerda que soy yo, cantando, ausente pero aquí,

cálido aún en el fuego de tu cuidado.

Dreaming in Swedish

The snow is falling on the tall pale reeds

near the seashore, and even though in places

the sky is heavy and dark, a pale sun

peeps through casting its yellow light

across the face of the waves coming in.

Someone has left a bicycle leaning

against the trunk of a sapling and gone

into the woods. The tracks of a man

disappear among the heavy pines and oaks,

a large-footed, slow man dragging

his right foot at an odd angle

as he makes for the one white cottage

that sends its plume of smoke skyward.

He must be the mailman. A canvas bag,

half-closed, sits upright in a wooden box

over the front wheel. The discrete

crystals of snow seep in one at a time

blurring the address of a single letter,

the one I wrote in California and mailed

though I knew it would never arrive on time.

What does this seashore near Malmö

have to do with us, and the white cottage

sealed up against the wind, and the snow

coming down all day without purpose

or need? There is our canvas sack of answers,

if only we could fit the letters to each other.

The simple truth

I bought a dollar and a half’s worth of small red potatoes,

took them home, boiled them in their jackets

and ate them for dinner with a little butter and salt.

Then I walked through the dried fields

on the edge of town. In middle June the light

hung on in the dark furrows at my feet,

and in the mountain oaks overhead the birds

were gathering for the night, the jays and mockers

squawking back and forth, the finches still darting

into the dusty light. The woman who sold me

the potatoes was from Poland; she was someone

out of my childhood in a pink spangled sweater and sunglasses

praising the perfection of all her fruits and vegetables

at the road-side stand and urging me to taste

even the pale, raw sweet corn trucked all the way,

she swore, from New Jersey. “Eat, eat”, she said,

“Even if you don’t I’ll say you did”.

Some things

you know all your life. They are so simple and true

they must be said without elegance, meter and rhyme,

they must be laid on the table beside the salt shaker,

the glass of water, the absence of light gathering

in the shadows of picture frames, they must be

naked and alone, they must stand for themselves.

My friend Henri and I arrived at this together in 1965

before I went away, before he began to kill himself,

and the two of us to betray our love. Can you taste

what I’m saying? It is onions or potatoes, a pinch

of simple salt, the wealth of melting butter, it is obvious,

it stays in the back of your throat like a truth

you never uttered because the time was always wrong,

it stays there for the rest of your life, unspoken,

made of that dirt we call earth, the metal we call salt,

in a form we have no words for, and you live on it.

My sister’s voice

Half asleep in my chair, I hear

a voice quiver the windowpane,

the same high cry of fear I first

heard beside the Guadalquivir

when I wakened to wind and rain

and called out to someone not there

and heard an answer. That was Spain

twenty-six years ago. The voice hers,

my sister’s, and now it’s come again

to ask how we go on without her.

That night beside the great river

I dressed in the dark and alone

left my family and walked till dawn

came, freezing, on the eastern rim

of mountains. I found no answer,

or learned never to ask, for

the wind answers itself if you

wait long enough. It turns one way,

then another, the trees bend, they

rise, the long grasses wave and bow,

all the voices you’ve ever heard

you hear again until you know

you’ve heard nothing. And so I wait

motionless, and as the air calms

my small, lost sister grows quiet,

as shy as she was in her life.

I remember coming back that night

in Sevilla past the rail yards,

trying to hold on to each word

she’d spoken even as the words fled

from my mouth. The switch engines

steamed in the cold. The sentry

in a brown cap sat up to shake

himself awake, and with no fire,

no human cry and no bird song,

the day broke over everything.

Ask for nothing

Instead walk alone in the evening

heading out of town toward the fields

asleep under a darkening sky;

the dust risen from your steps transforms

itself into a golden rain fallen

earthward as a gift from no known god.

The plane trees along the canal bank,

the few valley poplars, hold their breath

as you cross the wooden bridge that leads

nowhere you haven’t been, for this walk

repeats itself once or more a day.

That is why in the distance you see

beyond the first ridge of low hills

where nothing ever grows, men and women

astride mules, on horseback, some even

on foot, all the lost family you

never prayed to see, praying to see you,

chanting and singing to bring the moon

down into the last of the sunlight.

Behind you the windows of the town

blink on and off, the houses close down;

ahead the voices fade like music

over deep water, and then are gone;

even the sudden, tumbling finches

have fled into smoke, and the one road

whitened in moonlight leads everywhere.

Dust and memory

A small unshaven man, perhaps fifty,

with a peaked cap pulled sideways

to hide his features. He bowed his head

to the ground, groaned, rose to thrust

his head back in abandon, and flung

his body forward again. A supplicant

on his knees to what? The earth and sea

that had misused him? The power of pain?

The female God-face painted on the prow

of the fishing boat whose shade he hid in?

When the cap fell away I recognized a man

I passed each evening coming home at dusk,

a near neighbor to whom I’d never spoken

and never would. After dark I did not

steal back to find him gone or to hear

the sea, moonless, itself only a word

without consonants, repeated invisibly

inside my head.

What is this about?

Wherever you are now there is earth

somewhere beneath you waiting to take

the little you leave. This morning I rose

before dawn, dressed in the cold, washed

my face, ran a comb through my hair

and felt my skull underneath, unrelenting,

soon the home of nothing. The wind

that swirled the sand that day years ago

had a name that will outlast mine

by a thousand years, though made of air,

which is what I too shall become, hopefully,

air that says quietly in your ear,

“I’m dust and memory, your two neighbors

on this cold star”. That wind, the Levante,

will howl through the sockets of my skull

to make a peculiar music. When you hear it,

remember it’s me, singing, gone but here,

warm still in the fire of your care.

|

Colabora con nuestro trabajo Somos una asociación civil de carácter no lucrativo, que tiene por objeto principal la promoción y fomento educativo, cultural y artístico. En Rialta nos esforzamos por trabajar con el mayor rigor profesional en la gestión, procesamiento, edición y publicación de los contenidos y la información. Todos nuestros contenidos web son de acceso libre y gratuito. Cualquier contribución es muy valiosa para nuestro futuro. ¿Quieres (y puedes) apoyarnos? Da clic aquí. ¿Tienes otras ideas para ayudarnos? Escríbenos al correo [email protected]. |